The Wiggle

R. Cima, Ph.D.

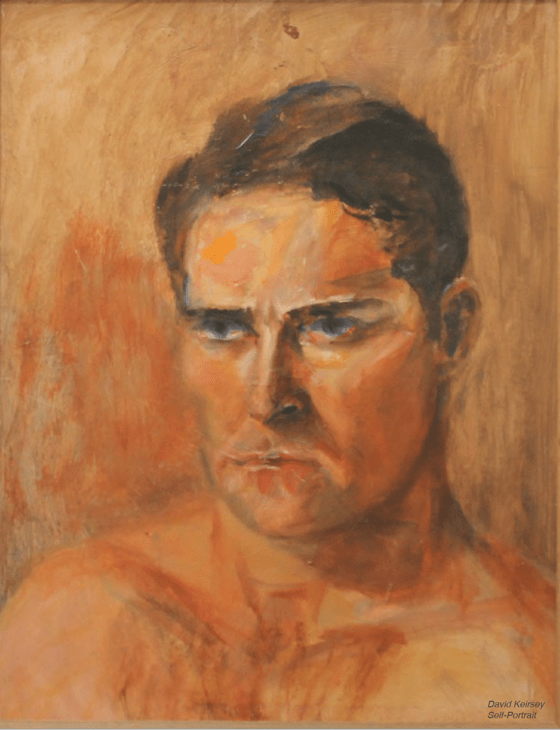

Editor’s Note: In this following essay by Randy Cima explains how he finally understood the concept of the Gestalt. My father, David West Keirsey, regarded himself as the last Gestalt Psychologist. Randy Cima, a student of my father’s, relates how he finally understood the concept in depth, and its importance in understanding human action. Personally, I am extending the concept in terms of Gestalt Science.

I once met with Dr. David Keirsey in his office at Cal-State Fullerton after class. He tried to explain something to me. I didn’t get it for several years. He told the following story.

He said he faced a similar dilemma many years prior. He said he had talked with Raymond Wheeler about holism, and what it meant. Wheeler, to a small minority, is considered to be the most important American psychologist. He is not well known. He is also difficult to read. Indeed, he did not write very much, even after much prodding by his colleagues. He also did not belong to the mainstream of traditional psychologists.

Traditional American psychology follows the reductionist view. What is essential is to understand the parts of the individual. For example, emotions, thoughts, motives, trauma, intelligence, behavior, and the like, are all said to be intricate parts of human beings, and each can be studied separately. While each certainly interacts with the other, often in less understood ways, each is a part.

The reductionist view is that it is the parts that make up the whole. A healthy, well-adjusted human being has successfully integrated these parts in a productive manner. This can be likened to the auto mechanic who successfully fixes a car. Perhaps it was the spark plugs, the camshaft, or the carburetor that was not working well. In the reductionist view, the therapist has the same function as the mechanic. He fixes parts that are “misfiring.”

Moreover, depending upon the particular reductionist stance taken, any one of these parts can become a focus of therapy. Each theorist will make the claim that this part is the most important part or is causing the other parts (and therefore the human being) to suffer. You only have to look at the number of different therapeutic approaches to notice that the reductionist view is prevalent in modem psychology.

In any event, I was interested in this new idea of holism. Keirsey continued his story. He apparently asked Wheeler the same type of question: what is holism? Keirsey then said: “Wheeler raised his hand and wiggled his index finger.” Keirsey smiled. I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. The perplexed look on my face must have been a clue.

He continued: Then he stopped wiggling his finger and asked me ‘where did the wiggle go’?

Keirsey smiled again. INTP’s have this annoying sense of humor. They seem to think the puzzle is more interesting than the solution.

I was polite and nodded. I also didn’t want to look stupid. Reclining on his couch, a favorite pose of NTs, he finished with: ‘That’s all I needed.”

At the same fifteen minute meeting, as I stood asking questions, he told me that Jay Haley’s Strategies of Psychotherapy was the most important written contribution to psychology in the past 200 years. He said that when he read it, “I had to throw away everything I knew and start all over again.” This from a man who had read everything written about the profession – twice.

I left the office.

I am a slow learner. I rather like it like that. Ray Choiniere once told me that I was like a dog with an old shoe, just chewing and chewing on the same five or six questions over a lifetime. That’s reasonably accurate.

I am also uncomfortable with puzzles. Always have been. While I read some, asked others, for the most part I thought about this meeting. I did read Haley five times, cover to cover, without stopping. I also read some of Watzlawick’s work, Parker’s brilliant Introduction to Theoretical Analysis, and others. I even read Vaahinger’s The Philosophy of As If at Keirsey’s urging. Vaahinger’s “truth is merely the most expedient error” ended my search for truth. Yet I was still unsatisfied.

While I was certain by now that psychology was not as yet a science by any stretch of the imagination, and that almost nothing was known of the human condition, I did not understand what holism was. Why? I was asking myself the wrong question.

Lately everyone claims to be “holistic.” It is fashion. The doctor, the therapist, the chiropractor, the hypnotist, and the acupuncturist all claim to be advocates of holism. People advertise using the phrase “a holistic approach.” Yet as I listened, read, and watched them, each still referred to the “parts” of the human being that are not working well. Could it be that they understood and I didn’t? What about that damn wiggle?

Then, one day, I got it. I don’t know how. It was like the first time I counted to 100, or read for the first time, or “got” multiplication in the fourth grade. It’s like a snapshot. I can tell you where I was, what direction I was facing, who was there, and what I said. Keep in mind I usually can’t recollect what I had I for breakfast. More intriguing than the puzzle, I cannot not remember discovery.

I was training a group of about eighty professional people. I began to talk about holism as compared to reductionism. The more I talked the more confused my words. I was nervous.

When I do training, I walk around. When I am nervous and training people, I walk around even more. I noticed I was walking. Then I stopped walking. Then I got the wiggle. Where did the “walk” go?

I had already read about “reification.” I understood what it meant. Webster’s New World Dictionary defines reify as: “to treat (an abstraction) as substantially existing, or as a concrete material object.” Not much of a definition, yet enough to get the idea.

A color is often said to have “body.” Sounds have “substance.” Common sense will tell us that look as we may, we’ll never see the body or the substance. It’s an abstraction. It has no size, no weight, takes up no space, cannot be touched, and you can’t describe it unless you use a metaphor of some sort. You can’t change it, modify it, rearrange it, operate on it, or do anything to the “body” of color or the “substance” of sound. We all know that.

Then I understood that traditional psychology is intent on defining abstractions. We are left to explain an abstraction with a metaphor. The brain is like a machine, with switches, containers, regulators, and so on. Human behavior can be explained as if we had an ego, id, and super-ego. Not unlike Pavlov’s dogs, all behavior is learned through conditioning mechanisms.

Then a giant leap of faith occurs. It is not scientific nor even particularly subtle. We begin to mend the metaphor. We say that there is a conflict, obstruction, or dysfunction that is occurring at or between the abstractions. Our metaphors are not working well. Our ego is listening to the super-ego. It is our repressions that need to surface -as if a repression is a thing that is stored, somewhere, accumulating with other repressions, “blocking,” simply by mass, normal behavior.

The “learning mechanism” is dysfunctional. The “switches” at the synapse are blocked by chemicals, or the lack of chemicals. The “centers” where reading, writing, or speaking abilities are stored are damaged. We need to “re-route” nerve impulses.

Where are these “switches?” No one knows. Can we diagram a “center.” Well, no. Do they exist? Sure. As abstractions, as a metaphor for “what it must be like,” as a way to explain otherwise unexplainable “structures” and “functions.”

The brain has had a wealth of metaphors. It used to be likened to the telegraph, the phonograph, the radio, the telephone, the television, and now the computer. Some newer writers are now comparing the brain to “holograms”

We are left to look for “connections,” “circuitry,” “transistor-like structures,” and the like. Scientists essentially are mechanics, looking for broken parts in this reductionist view.

Lashley took a lifetime to find the “engram.” This was where the brain stored information. It had a structure, and it had a place. Towards the end of his life, after decades of investigation, he gave up the search saying that “it,” the engram, was not there. Yet, today, many still refer to this “structure” that has the “function” of storing information.

That was the difference between holism and reductionism. The types of metaphors the scientists used! Reductionists posit thing abstractions, consider them as if they are “structures,” give them names, figure out what they “do,” try to find them “someplace,” and begin to repair them. What is remarkable is how much “repair” is done without ever seeing the structure.

Holistic psychologists posit action metaphors. People don’t “have” things. They do things.

The wiggle didn’t go anywhere. The wiggle was never there. It was an activity. That’s what was wrong with my question. I was looking for something.

I bend my arm. Do I have a “flex?” Is there something wrong with my “flexing mechanism” if I can’t? Only if I consider the abstraction no longer an abstraction. Once I say there is something wrong the the “mechanism,” that I have a broken “flex,” or that I have “hypoflex,” I have to figure out some what to fix “it.”

Then where is “hyperactivity?” How do I get “it” out? How do I effect “it?” I can’t. “It” isn’t there either. Holistic psychologists would say the same is true for “schizophrenia,” “depression,” “paranoia,” and all of DSM III. People don’t have dysfunctions, people do dysfunctions. In fact, you can’t use the word “dysfunction!”

Then how do you explain “crazy” behavior if there isn’t something wrong with the mechanisms or structures or functions or some other “tangibles.” Rather than “dysfunction,” holists will say there is a disturbance of consciousness, or there is a disturbance of affect. But, that’s a longer story yet.

I can tell you this. After this much time, I am sure the mechanisms, structures, functions and other tangibles aren’t tangible at all. I am also sure the holistic explanation for the “mad” experiences of people is more cogent, consistent, and humane. At least as far as I’m concerned.

Ray Choiniere tells his own story, perhaps as revealing. As a new school psychologist many years ago he received a common directive from his supervisor. “Fix that child.” This particular child was a non-reader. He obviously had a “learning handicap.” That was the thing to fix. The “handicap.” Ray wanted to make a good impression.

Forget that like the good metaphor it is, the “handicap” has no size, no weight, takes up no space, cannot be touched, and you can’t describe it unless you use a metaphor of some sort, Ray was to fix “it.” The supervisor said the child was dumb as a stump. Within several months, the child was reading well.

Ray said he sat down with the child every day and taught him to read.

Where was the “handicap?” The same place as the wiggle.